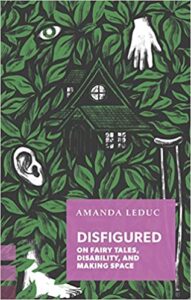

Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space by Amanda Leduc ( Bookshop.org | Amazon.com )

Coach House Books, 2020

ISBN-13 : 978-1552453957

Available: Paperback, audiobook, Kindle edition

Although Disfigured focuses on the relationship between fairy tales and disability, there is a lot here that should provide food for thought in the horror genre, where disfigurement, disability, and illness are often used to indicate otherness, villainy, or monstrosity. Leduc examines well-known, mostly Western fairytale archetypes from literature and pop culture, how and why they were created, and the damage those narratives can do to perceptions and treatment of disabled individuals, using a disability rights framework. She explains that this is not a work of fairy tale scholarship or of an expert on disability rights, but that she approaches it as an individual who has loved fairy tales for most of her life and is physically disabled, with major depressive disorder. As a white disabled woman, she notes that her ability to comment on the impact of Western fairy tale narratives is limited, and that there needs to be space for and attention paid to the perspectives and experiences of disabled people with multiple marginalizations about the impact these narratives have had on them as well.

Interspersed with her research and analysis are medical notes taken by the doctor Leduc’s parents consulted regarding her diagnosis and neurosurgery at the age of four, and autobiographical writings describing her childhood and young adulthood and how storytelling and fairy tales impacted her. This is an interesting structure, which personalizes the book, but it does lead to an idiosyncratic organzation of the material, with a fair amount of repetition. Leduc writes that “disabled identity is… inextricably bound up with how someone navigates the world,” literally, in her case, as she has cerebal palsy. Who tells her story and how cannot help shaping her view of who she is and will be, and the stories around her, and many other disabled people, also give them messages about their places in the world. As a child, many of those stories are fairy tales. Leduc writes that “we have used this storytelling form to illustrate that which is different; whether that difference is disfigurement or social exclusion, fairy tales often centre in some way on protagonists who are set apart from the rest of the world.”

In some stories, like “Hans My Hedgehog”, the protagonist, who is half-hedgehog, is treated cruelly and excluded as a child, even after he leaves home, excels, and shows himself to be generous. It is only after he is accepted by a princess in his half-hedgehog form that he reveals that he is actually a handsome young man. His transformation into an attractively formed man is his happy ending. Characters who are disfigured, disabled, or part-human(either born that way or as a punishment) often have this “happy ending”, (if they get one) that implies that there can be no happy ending without individual transformation to a fully functional, attractive human, even if a price must be paid. Leduc suggests that while that is a destructive message in general, it is particularly damaging to disabled people who grow up with fairy tales. In these stories, society doesn’t become more accessible; it’s the individual who must change, and sometimes that change isn’t possible (or preferable) on an individual level. Leduc does a nice job of explaining different models and theories of disability, such as the medical model, charity model, psychological theories, social model, and complex embodiment (although not all in the same place. I suggest lots of bookmarks for this book).

Leduc says stories can be told in a way that calls for community and social structures to change so that anyone can succeed, or they can be told in a way that privileges individual triumph. She contends that under the surface, we have been taught through our stories that to be disabled is to be lesser, filled with darkness, and in pain, and therefore unhappy. Even when fairy tales have been written subversively, to encourage the disenfranchised, disabled people have still been represented as either pitiable, inspirational, or villainous. Leduc concludes that in real life, a disabled person isn’t necessarily transformed for a happy ending or permanently villainous. There is a complex, lived experience in the disabled body that isn’t represented by flattened archetypes and ableist language and symbolism, and she calls for envisioning these traditional stories in ways that make space for a new kind of fairy tale that does not privilege able-bodied, conventionally attractive characters or assume that happy endings are all identical.

Horror and dark fiction face some of the same issues. Protagonists are often set apart from the community by some kind of flaw, monsters and villains are often masked, disfigured, or disabled in some way, and the stories can have flattened characters or depend on “shortcut” tropes to quickly communicate a story’s schema to a reader or watcher. Leduc examines this through the lens of Disney villains and heroines, and superheroes, but in the horror genre we see it in many of the great villains and protagonists of horror and Gothic literature and cinema such as the Phantom of the Opera, the Invisible Man, Frankenstein’s creature, Quasimodo, and more. Just as horror and dark fiction are making space for more versatile representations and stories with BIPOC characters and authors, we need to ensure that there is also space for new kinds of representations and reimagined stories with disabled characters and authors (and also where those intersect). There is food for thought here for those creating and consuming in the horror community.

Be cautioned that this is a long book, however. Leduc’s personal story is interwoven in many places so that it’s hard to skip around to just find the analysis and commentary on fairy tales and how they fit with the disability rights framework. This is deliberate, and while it’s interesting as a memoir, if you plan to use this book as a reference, it can get frustrating. As a disabled person who has been a children’s librarian and elementary school media specialist, has a Disney-obsessed daughter, and has been thinking about how disabled people are represented in horror fiction for quite some time, I found this to be a worthwhile and fairly unique read (Amazon shows me just one other book on this topic, a more narrowly focused academic study, and only a few on disability and horror), and it’s an intriguing topic, so I hope it is finding its audience. Recommended.

.

Follow Us!