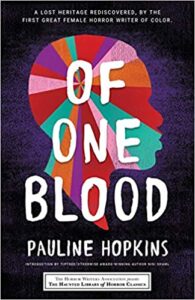

Of One Blood: The Hidden Self (Haunted Library Horror Classics) by Pauline Hopkins, edited by Eric J. Guignard and Leslie S. Klinger, introduction by Nisi Shawl

Poisoned Pen Press, 2021

ISBN-13 : 978-1464215063

Available: Paperback, Kindle edition

This new edition of Of One Blood is part of a series published by Poisoned Pen Press in partnership with the Horror Writers of America. Author Pauline Hopkins was an African-American writer of the early 20th century, and Nisi Shawl introduces the book, originally published in chapters as a serial in The Colored American magazine during 1902-1903, as an early speculative fiction novel combining the popular genre of “society novels” with a “lost world” narrative. revolutionary because the “lost world” is an advanced society consisting entirely of Black individuals, and promoting the thesis, novel at the time, that Africa is where the arts and technology have their origins.

Set in Boston in 1891 (my best guess based on the footnotes), Reuel Briggs is an impoverished medical student passing as white who is obsessed with the hidden forces of the supernatural and how to control them enough to reanimate the recently dead (shades of Victor Frankenstein). He is given the opportunity to put his theories into practice when the beautiful African-American singer Dianthe Lusk is killed in a car accident. While he is successful at bringing her back to life, she has lost her memory, and Reuel, his wealthy friend Aubrey, and Aubrey’s fiance Molly, set out to rebuild her into a new person. Molly becomes close friends with Dianthe, and Dianthe and Reuel fall in love and marry. To support her, he appeals to Aubrey for help in finding work. Aubrey, secretly in love with Dianthe, gets Reuel to sign on to a two year expedition to Africa to get him out of the way so he can marry Dianthe himself.

As Reuel journeys through Africa he sees its greatness, vividly described by Hopkins. The white men he is traveling with are surprised and at first dismayed to realize that African civilizations and peoples are the cradle of culture, as they have always believed that Africans were lesser than white people. Through Aubrey’s machinations, Reuel and Dianthe receive letters informing them that the other is dead, but while Reuel’s supernatural and mystical powers grow, Dianthe feels more and more lost and traumatized, especially as she learns more about her tangled family tree.

There are many books now that deal with the intergenerational trauma, tangled family trees, and family separation caused by slavery, including Octavia Butler’s speculative novel Kindred, Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing, and Maisy Card’s These Ghosts Are Family. In Of One Blood, we see a fantastical, awe-inspiring world, that contrasts the glories of African civilization rising again with the results of the terrible treatment, taken for granted, of African-Americans. Dianthe in particular goes through unbelievable trauma: she is killed, re-animated, separated from everything she knows, nearly drowned, grieving a friend and a husband, and under tremendous pressure from Aubrey already, when the additional information about her family comes to light. In her case, it only takes one generation to destabilize her and poison her interactions with her environment. Shawl described this novel as science fiction, but to me it seems more to combine the “lost world” utopian narrative Reuel experiences in Africa with the Gothic horror experienced by Dianthe.

Occasional footnotes are helpful in dating the time period of the book and understanding vocabulary and literary references. A brief but detailed biographical note about the author, discussion questions, and a wide-ranging list of recommended further reading follow the story.

This is a good choice for readers interested in the beginnings of Afrofuturism and African-American speculative fiction and horror, Gothic horror, lost world and utopian narratives, and early 20th century African-American and women writers. In addition, Of One Blood would be a unique choice for the increasing number of book clubs focusing on anti-racist titles, which, in my experience, generally avoid genre fiction. Highly recommended.

Contains: incest

Reviewed by Kirsten Kowalewski

Follow Us!