Grady Hendrix’s novels include Horrorstor, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, and We Sold Our Souls. He has also written the nonfiction title Paperbacks from Hell. His most recent publication is The Southern B ook Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires. Recently, Monster Librarian reviewer Lizzy Walker had the opportunity to interview him.

ook Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires. Recently, Monster Librarian reviewer Lizzy Walker had the opportunity to interview him.

Interview with Grady Hendrix

LW: I watched both your Night Worms and Raven Books sponsored events. At the first one, you showed your bankers boxes of paperbacks. How long did it take you to acquire them, and how much went into creating Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires? What other materials did you use for research to write this book?

GH: It’s weird, because I wasn’t a big horror guy growing up. I read Stephen King and stuff, but I sort of thought the covers were too gross. I just wasn’t a fan. I noticed that once I was writing horror I would go into paperback shops and see all these horror titles and authors I had never heard of, books I’d never seen. I wanted to figure out what all this stuff was, so I started reading random books and writing about them for Tor. After a conversation with my editor at Quirk Books, pitched Paperbacks from Hell which came between My Best Friend’s Exorcism and We Sold Our Souls on our contract. I had about ten months to educate myself on these books and write. I read 236 or something like that in that period, and then that addiction kind of stuck. I keep buying these books and I can’t seem to stop. It’s really irrational.

When I got ready to write Southern Book Club, those books didn’t have much to do with it. . I did a whole other set of reading for Southern Book Club. A lot of that was vampire folklore, Dracula, and tons of domestic fiction, stuff like Erma Bombeck, Nancy Stall, Shirley Jackson’s Raising Demons and Life Among the Savages, Florence King’s Confessions of a Failed Southern Lady, books that were popular in the ’70s and ’80s that were a housewife writing about being a housewife. I also read a ton of true crime, because that’s not a genre I was really familiar with. Now that I’m doing a lot of events on vampires, it’s fun to revisit them and talk about them to help promote the book.

LW: Why vampires for Southern Book Club?

GH: I always knew it was going to be a vampire for this one. I had the title for this book before I had anything. The original title was My Mom’s Book Club Killed Dracula. When you get to solo monsters, there’s not a lot of them that can pass for human, right? There are werewolves, but with werewolves you have so many logistical problems. Like, once a month? Really? That’s it? So, you have a book that’s unfolding over months and months and months, and a vampire was just sort of instinctual. Then it sort of came together and as I was doing my research I was like, vampires are just essentially serial killers. They pass for human, they use other people as objects, they regard people as lesser beings than themselves. To a vampire, humans don’t even rate. It’s the same way serial killers dehumanize their victims.

LW: You mentioned that you wrote from experience when it came to Miss Mary and life experience with your own grandmother. How much of your personal experience came into play with this book?

GH: The South is certainly somewhere I know very well. I’ve always been sort of irritated by depictions of the South that are very cartoony. If the best you can do is scratch the surface and you can’t get beyond that, why are you spending time and effort on something that you can’t depict with any depth? Every character in my book starts as a real person. It may be someone I saw on the subway or pass on the street, or it might be someone I’ve known for a long time. By the time they get on the page, they’re so heavily fictionalized that no one ever recognizes themselves.

With Southern Book Club, I felt that I had to run this past my family because there are a lot of fictionalized family stories in it. Two things cut closest to the bone in the book. Miss Mary is based on my dad’s mother who lived with us for about three years when I was a kid when she couldn’t live on her own anymore. Now we know it was Alzheimer’s, but at the time it was “Well, she’s old. Old people get flaky”. I knew that I loved my grandmother and I was told she and I were close when I was very young, but by the time she came to live with us, I was 8 or 9 and I was terrified of her. She was very angry and frustrated because of her physical and mental limitations. When you’re a kid you really crave for things to be the same every day. You want a routine and my grandmother was enormously disruptive to that. My mom did her best, and she felt that having her integrated with us, having dinner with us and all that, was the way to go. She was probably right, but what it meant was that there wasn’t a big separation. She seemed like a monster to me. So, I wanted to write a book that gave her a moment in the sun. It’s me sort of writing through that stuff, but I also don’t see that often in books.

One of my in-laws once said to me, “How come people in books never have siblings?” And she was right. It’s hard say here’s my main character, and they have a brother, and they also have parents. But I feel like that’s real, so I wanted to get all of that in there. It’s funny, it made the book hard to write, because other drafts were epically long. The first draft was almost 200,000 words because it spent time with every family. If you’re going to do that, you have to know their whole structure, you have to know their siblings and where they fall in the family. I mean, good God, I have so much about Kitty’s family it’s unbelievable. The good part of that is that it made me think through the back stories for everyone. When Kitty shows up on the page, I know where she’s coming from, I know what she’s done that day, I know which of her kids is getting on her nerves, I know which of her kids she likes at the moment. It really helps me to have that stuff.

LW: All the women seemed very fleshed out. I was never confused about who was talking. They all have their distinct personalities. Everybody felt unique.

GH: Good! I always start writing a book and I don’t have that stuff and I hit a point halfway or two-thirds through the first draft where I get really frustrated and then I go back and spend weeks just working out everyone’s backstory. So, I’m glad that came across.

LW: What made you focus on Patricia out of all of them?

GH: Patricia is the most like my mom in some ways, but there are deep differences. Patricia is a former nurse who’s married to a doctor, is a housewife, and taking care of a family and her mother-in-law. I mean, that’s my mom’s life in outline form. A lot of it diverges, and that’s one of the hard things with basing characters on people I know and with traits of people I know is that it’s hard for me to let them go, and sort of come alive within the confines of the book. By the time the book is over Patricia is so radically different from my mom because of the events of the book. I wanted to take someone with a similar background, someone I knew and understood, and sort of put them through the wringer and see what’s left of their world when they come out on the other side, if that makes any sense. It sounds really sadistic. One of the things that’s weird to me is that everyone’s life falls apart a couple of times. I wanted to explore what happens after everything falls apart. I’m really interested in Regan and her mother’s road trip after they leave the house in The Exorcist after the end. I’m really curious how that was. Like, was that fun? Did you guys have a lot to talk about? What happens after you rub your mother’s face in your bloody crotch? Like, where does the relationship go from there?

LW: I might be trying to make connections where there aren’t any, but am I right in making an accurate comparison to Charlotte Perkins Gillman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, especially with Patricia and her husband where he brings her the Prozac? For some reason that just connected the two plots together for me.

GH: The Yellow Wallpaper is a story I love, so that may have been an unconscious influence, but it’s also unfortunately how things are sometimes. I know more than one true story about a psychiatrist having his wife committed because he’s tired of her. I’m not saying they all happened in my neighborhood, but in the 40s, 50s, 60s, and even into the 70s and 80s, it wasn’t unknown. In my town, Charleston, doctors were treated like kings and had a lot of authority. I don’t think it’s uncommon to say people overmedicate. What year did the Rolling Stones sing “Mother’s Little Helper”, you know? There has always been a tradition of medicating women who are “unhappy”. Mary Daly writes a lot about it in her books, about this sense of women feeling uneasy with the world around them because the systems in the world aren’t made for them. But this unease sometimes gets diagnosed as a disease, and what do you do with the disease? You have medicine for it. I read a ton of books from the 90s trying to get into the mindset of the big nonfiction on-trend books, like The Erotic Silence of the American Wife, Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus, and also Prozac Nation, which was bizarre. It’s written by a psychiatrist and it’s basically this ode to the glories of Prozac, which we weren’t even sure what the side effects were, but this book was a big bestseller and the message was, everyone should take Prozac. It’ll just make you happier. There was this idea, especially in the 90s, that a pill could fix things. We weren’t sure how, and we weren’t sure what was getting fixed, but this pill could do it. I think that fit in well with the idea of the 90s being a time when we were looking for easy solutions. In the 80s we were looking for easy solutions, but we didn’t have them yet, and in the 90s we thought we had easy solutions…like Prozac.

LW: Talk about James as a vampire. It’s interesting that you mentioned elsewhere that you relied on the power of the patriarchy rather than any type of supernatural powers of persuasion. What made you address vampirism in this way?

GH: I wanted James Harris to be a non-supernatural vampire, which meant he can’t turn into a bat, he’s not scared of religious symbols, he has a reflection. But there were two places I fudged a little bit. One is that he needs to be invited in. For him it’s become a habit and a custom. He can come inside your house uninvited but he really, really prefers not to. In his mind, he justifies his behavior by never going where he’s not invited. To him, everyone’s “asking for it.” I also liked playing with the idea of him controlling people’s minds. He doesn’t technically have mind control powers, but he has enormous force of will and, like a lot of men, he’s very very good at pressuring women into doing things they don’t want to do.

LW: Can you talk about the representation of African Americans in the book?

GH: Sure. One of the things with the book is that James makes a really calculated decision. He’s a vampire, and he realizes that a time is coming when living on the margins doesn’t fly anymore, when he’s going to have to have a photo ID, and a credit card, and that means he needs a Social Security number, a birth certificate, that whole bunch of stuff that we all take for granted now. That need didn’t really exist to a great extent in the 80s, and I think up through the 80s there were still drivers’ licenses that were cardboard, you know? This idea of living on the margins was fun, as long as you’re happy on the margins. James sees that a time is coming when he’ll need to put down roots, and he decides that the place to do that is a small Southern town where, as a white guy, people are going to be more willing to take him at face value. He realizes that as long as he limits his feeding to marginalized people, the poor working class and largely, in South Carolina, at that time, the African American population he thinks he will be fine. Who is going to notice that? Who is going to care? To some extent, he’s right.

One of the interesting things I’ve seen coming out of reporting since probably the 2010s is a lot of serial killers are coming to light who preyed on African Americans. It was viewed formerly as a white thing, serial killers were white guys, and what is slowly coming to light is there are African American serial killers and have been, but largely their victims go unreported and the crimes don’t go above the surface level of investigation. There was a series of unincorporated townships in North Carolina where African American prostitutes were being murdered, but because they were poor and African American, and because these townships had jurisdiction issues, it wasn’t investigated the way, say, the Son of Sam killings were investigated. I get why that happened, but what James Harris doesn’t understand with his surface level view of the South and the way it works, is that upper middle class white women in the 90s and in South Carolina really relied on working class African American women to clean their houses, help raise their kids, help them run their errands, take care of their elderly relatives. Those women became integrated into their families.

One of the people closest to my grandmother was this guy Luther who was an African American guy who took care of her garden plot. He would weed, he worked on her house, and he did this for a few other women, but he was really close to my grandmother. However, he wasn’t allowed in her house. Part of it was because he was a man and she was a widow and didn’t want a man in her house who wasn’t a relative, but the other part was that he was Black. And that’s a real contradiction. So, yes, my grandmother was racist. At the same time, she also had a much closer relationship with Luther than a lot of people did, so it’s a weird thing to parse, and it’s not binary, like on or off. A lot of these friendships, like people like Patricia have with Mrs. Greene, they’re very bound and limited by issues of class and race, 100%. The time Mrs. Green spends taking care of Patricia’s family is time taken away from her own family. So it’s really rough. At the same time they genuinely care for each other and have a real respect for each other within those limitations. It was a tricky thing for me to write because it’s very easy to get wrong. At the same time, I couldn’t have written this book without it because that’s how it was, and that’s what I saw. It’s one of those topics that I wanted to be very careful about and present from my point of view. I certainly could not write from Mrs. Greene’s personal experience, but I wanted readers to know that she was a proud, independent, hard working woman while at the same time being a victim of forces outside her control.

To me it’s funny, Stephen King does kind of the same thing with the character Mike in IT. Mike’s the one who stays behind and sounds the warnings, and it renders him kind of a passive character and I was really bummed in the movie to see that he was still kind of passive that way. Mrs. Greene and other people in Six Mile see what’s happening first. They see the warning signs of this first with what is going on with James Harris, and they are the ones who keep going and keep investigating, keep looking into it, keep drawing attention to it, which I think is tremendously brave and a tremendously active thing to do. It’s something we are seeing right now, where we see poor marginalized communities as the ones getting hit first by things like climate change. They’re the ones getting hit first by a lot of the economic realities people are facing now. I feel like when people are saying, “Wow, it’s really hard to work and take care of my kids right now in this pandemic,” I feel like working class women who are single moms have been telling us this for a long, long time. We just haven’t been listening. I get that it’s not a sweet picture, and I wanted to make sure I didn’t screw it up and I still don’t know if I have. But I had to be honest with my own perception. I feel like as long as I kept it from my point of view, that I was satisfied that I wasn’t overstepping, but that isn’t to say that I didn’t.

LW: My Best Friend’s Exorcism is set in the same universe/world. Can you talk about why you made this decision?

GH: After My Best Friend’s Exorcism, I really wanted to write an adult book. That book was about teenage friendship and everything was from a teenage friendship point of view and I wanted to write one about adult friendship, or a parent’s point of view. I also wanted to return to that neighborhood just because that’s where I grew up during the time period roughly, so I know it very well. I know it, so I see all the warts and I know what is what, and I know my bearings there, but I also find it tremendously comforting, that time period and that location.

LW: What projects are you working on now?

GH: I’ve got two books under contract right now, one for 2021 and one for 2022, and then I have a book that I’m working on that’s a nonfiction that’s a little bit like Paperbacks from Hell but on the rise and fall of kung-fu movies coming to America in the 70s and 80s. I’m working with a cowriter who is a collector and really knows his field, and it’s going to be a heavily illustrated book. The next book is written, I’m just doing some revisions and that one will be out in summer 2021. As soon as I’m done with those revisions, I will start on the book for 2022. I can’t say a ton about them because they haven’t been announced yet, but the book for 2021 is sort of an angrier book and much more in the vein of We Sold Our Souls. The book for 2022 is more about families and much more like Southern Book Club. I’m excited to finish up the revisions and then dig into the new book.

LW: What are you reading right now?

GH: I’mreading a lot of vampire material to be able to do events promoting Southern Book Club. I find myself reading mostly comedy and a lot of domestic novels. I’m also reading a lot of folk horror. There’s been a folk horror project I want to work on that’s at least two books away if not three, so maybe that is seeding the ground for that.

One book that has had an enormous influence on the book coming out in 2022 is Kier-La Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women. The way she makes her personal history tie into horror and all that is really, really fascinating. I think it was a little ahead of its time to be honest. I think it got regarded as a genre publication and I don’t think it is. I think it has a bigger reach outside the horror audience.

LW: Since you were on the Summer Scares committee last year, would you have any recommendations for this year, including kids and teens titles?

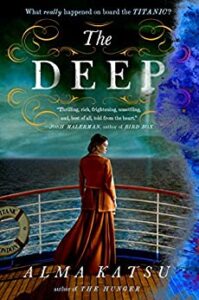

GH: Alma Katsu’s The Deep is one I enjoyed just because I love shipwrecks and water horror. I loved Stephen Graham-Jones’ The Only Good Indians that is coming out in July which is a great blue collar reservation life novel that also happens to have a shapeshifting elk woman in it, and a lot of basketball. I feel like know basketball now. I’m curious to see how people respond to Paul Tremblay’s new book, which is about a pandemic, Survivor Song, that is also coming out in July. One of the things that I always have a real bugbear about, I get depressed about how often we lose boys who read in their teens because they would rather play Fornite or Call of Duty, and I would have frankly, too, if those games had been around when I was a teenager. I think what happens is you wind up with fewer books getting aimed at boys, so they’re finding less to read. But, one of the books that really blew my mind and that would have spoken to me as a 13-year-old boy, is called Rotters by Daniel Krauss. It’s YA, and it’s about a kid whose mom dies, and then he has to go live with his dad who he doesn’t like or know very well. They bond over his dad’s career as a graverobber, and not like coaches, and velvet cloaks, and shovels at midnight graverobbing, but getting in there with a wood chisel and knocking out gold teeth and living in squalor surrounded by stuff that smells like formaldehyde. It is one of the most punk rock books I have ever read in my life. It is so antisocial and so full of loathing for everything we as a society prioritize, like cleanliness, politeness, respect for the dead, not cutting of dead people’s fingers with bold cutters. It’s one of the very few books I’ve ever had to put down because I got so uncomfortable at one point. If I would have read this at 13 or 14, it would have changed my life. So, if you’ve got a boy in your life who is having trouble reading, maybe it’s because they’re not finding stuff they want to read, and I think Rotters is really great.

LW: Do you have anything else you want Monster Librarian readers to know?

GH: Right now, I think it’s important for people to support their local independent bookstores. I love Amazon, I order from them all the time, but Amazon will be around next year. A lot of independent bookstores might not be, and a lot of them right now are using bookshop.org for their fulfillment and online services and it has been amazing to me to see all these brick and mortar stores turn on a dime and become mail order businesses, doing home delivery and curbside pickup, hosting virtual events, and making all of these changes. Yes, if you by Southern Book Club from an independent bookstore, it’s probably going to be $22 and maybe $15 or $16 on Amazon, but the fact is that extra $5 is the price we pay to support or neighbors and people we know in the community. Book stores are really doubling down on serving their neighborhoods and communities. I think that is amazing, and without them I think we’re all going to be really sad because they will not come back when they’re gone. So, if I can encourage anyone to do anything, just take $25 from your stimulus check and buy a book from a local bookstore.

Follow Us!