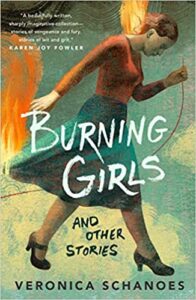

Burning Girls and Other Stories by Veronica Schanoes with a foreword by Jane Yolen

Tor.com, 2021

ISBN-13 : 978-1250781505

Available: Hardcover, paperback, Kindle edition, audiobook ( Bookshop.org | Amazon.com )

In Burning Girls and Other Stories, Veronica Schanoes brings the present day into a literary and folkloric past that brings fairytales, history, and Jewish tradition together to form something new and unique. I don’t think I have ever encountered new tales that blend Jewish tradition, history and religion in a way that feels familiar to me as a Jew, and the stories in the book that use this technique are, I think, the strongest ones in the book.

I had read the titular novella, Burning Girls, when it was originally published, and was wowed by it at the time (I was not the only one, it was nominated for a Nebula and World Fantasy Award and won the Shirley Jackson Award for best novella). In this story, a young woman who has been trained by her grandmother in herb lore, Jewish women’s rituals, and witchcraft, immigrates to the United States. Her sister has signed a contract with a lilit, a demon that steals children, and must discover the lilit’s name to break the contract. In addition to the religious lore, Schanoes interweaves the sewing factories’ unsafe conditions in the early 20th century, the growth of socialism, and the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. The transformation of a Grimm’s fairytale into a story of Russian Jews’ immigration to and intergration in America created a stunning, tragic, and relevant story.

In Among the Thorns, Schanoes responds to an antisemitic story that appears in Grimm’s Fairy Tales, “The Jew Among Thorns”, in which a youth is rewarded by a dwarf with a fiddle that enchants anyone who hears it into dancing, a fowling piece that never misses, and the ability to have any request granted. He meets a Jew in the road and forces him to dance in nearby thornbushes and hand over his money. When the Jew lodges a complaint in the nearest village, and the youth is sentenced to hang, he plays the fiddle again, enchanting the town into dancing and using his power to have the Jew hanged instead. Schanoes’ story is told from the point of view of the daughter of the victim, who agrees to a bargain with the Matronit, or Shekina, the goddess of Israel who appears in the Jewish Kabbalah, so she can take revenge on the fiddler and the town. What’s most chilling in this story is the context in which it’s set. While much of the story may seem just a tale, the first page mentions names and dates: the actual incidents may be fictional, but the antisemitism and antisemitic violence were not.

Emma Goldman Takes Tea with Baba Yaga is a wonderful metanarrative in which Schanoes plays with the conventions of fairytales and narrative nonfiction. Emma Goldman was a Jewish immigrant from Russia in the early 20th century who was a notorious anti-capitalist anarchist and was deported back to Russia after many years of activism in the United States, only to become disillusioned with the Russian Revolution. Schanoes begins by attempting to write Emma’s story in a fairytale format, but Goldman is a real and vivid figure in American history, and the details of her life are too important for that. Schanoes imagines Goldman, tired and disillusioned, meeting another controversial and legendary figure, Baba Yaga, and what that meeting would be like. As a fan of both, I really enjoyed this. Schanoes also takes this opportunity to speak directly to her readers about the impact of Marxism and revolution on the present day and her own beliefs, an interesting choice.

Phosphorous does not touch on Jewish religion or tradition, but is also a strong story. It describes the events and environment of the London matchgirl strike of 1888, both from a third-person narrator’s point of view and from the point of view of Lucy, one of the striking workers who is fatally ill, deteriorating quickly due to her close contact with the white phosphorous the matches are made with. Her grandmother comes up with a terrible plan to keep Lucy alive long enough for her to see the end of the strike. Schanoes grounds this story in historical fact by including real people such as Annie Besant as characters, and suggesting that physical artifacts exist as evidence of the story.

Schanoes’ ability to seamlessly draw real events and people together with folklore and fairytale, even while breaking the fourth wall, is impressive. Other stories I haven’t described in detail seem hallucinatory, playing with language and imagery while also using literary or folkloric elements, such as Alice: A Fantasia and Serpents. Jane Yolen’s praise in the introduction that these stories have a “lyric beauty” that “bleeds onto the pages” is well-deserved.

Highly recommended.

Reviewed by Kirsten Kowalewski

Follow Us!