The reason I went back to school after working as a children’s librarian in a public library was that I noticed that sometime around grade four kids stopped coming to the library, They were too busy, they had too much homework, they had stuff going on. Even programs carefully designed around their interests weren’t attracting those kids.

I wanted to reach those kids. And I was willing to quit my job and go back to school to reach them where they were– school– a captive audience I could finally reach. And I did. But even in 2005, the librarians were the first ones to go when the budget got sliced.

In grad school and through 2005 I was part of a children’s choice committee for grades 4-6. We had a list of books proposed that we had to read, evaluate, discuss, and eventually choose 20 books for our nomination list. Kids who read at least 5 could vote for their choice for best book. And the book with the most votes won the award.

Where am I going with this?

I currently volunteer in my kids’ former middle school library.

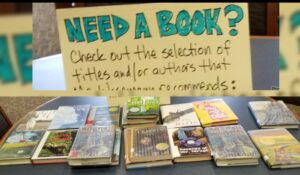

In early February I was asked to pull teacher favorites for a display. These included many of what would be considered classics- To Kill a Mockingbord, Night, The Call of the Wild, 1984, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Only two of them had been written since 2005.

In mid-February, a teacher put a table of best books out on a table These were great choices I would have no problem recommending. But I recognized almost all of them as books I had read while on the children’s choice committee. Only a few had been written in the last five years. One (Scythe) is taught as required reading at the high school.

We are not reaching teachers. They may be tolerating or even accepting horror in their classrooms but many aren’t promoting or providing horror genre titles to their students. And teachers have a huge influence on what gets checked out. It has to be a cooperative effort. The media specialist had a virtual visit with students with Lorien Lawrence in February, but on the day I came in, his books were still on the shelf.

I have helped the media specialist pull and promote scary and horror-themed books in the past. At the elementary, there’s time for storytelling to shape readers. But that isn’t enough at the secondary level. How do we reach teachers, especially at a time when giving kids books is so dangerous? It’s time to think outside the box.

Editor’s note: I have had this characterized as a “diatribe against teachers”. It’s not. Teachers have a difficult job that is being made harder by conservative school boards and state legislatures. There is currently an effort to pass a law that would criminalize teachers and librarians for giving students “inappropriate” books in my state. Many school and classroom libraries have been cleared away elsewhere.

Teachers face the difficulty of finding reading material their students will find relevant and engaging within challenging restraints. 20 years ago I was working to convince other school librarians horror was relevant and had the potential to be engaging to their students. Today there’s a Librarian’s Day at StokerCon: librarians are engaged in collection development and promoting the horror genre. I am asking, where do we, as members of the horror community, go from here? What can we do to help?

Follow Us!